|

|

Greetings and salutations everyone and welcome to another blog here on BlueCollarBlueShirts.com. A special guest posting tonight!

Friend, peer, hockey historian and fellow co-author, Ty Dilello (you can find his books on Amazon here: Amazon.com and you can find his website here: https://nhlhistory.substack.com/about ), recently shared a piece on his website in regards to former Ranger Ching Johnson.

The following, while on his website today, first appeared in his book Golden Boys: Manitoba Top 50 Players

While Dilello’s expertise is in Winnipeg/Manitoba hockey history, I found his article on the legendary Ivan “Ching” Johnson worth reprinting here.

With his permission, here’s the article – and a “T.Y.” to Ty for allowing me to share with you guys and gals on this site!

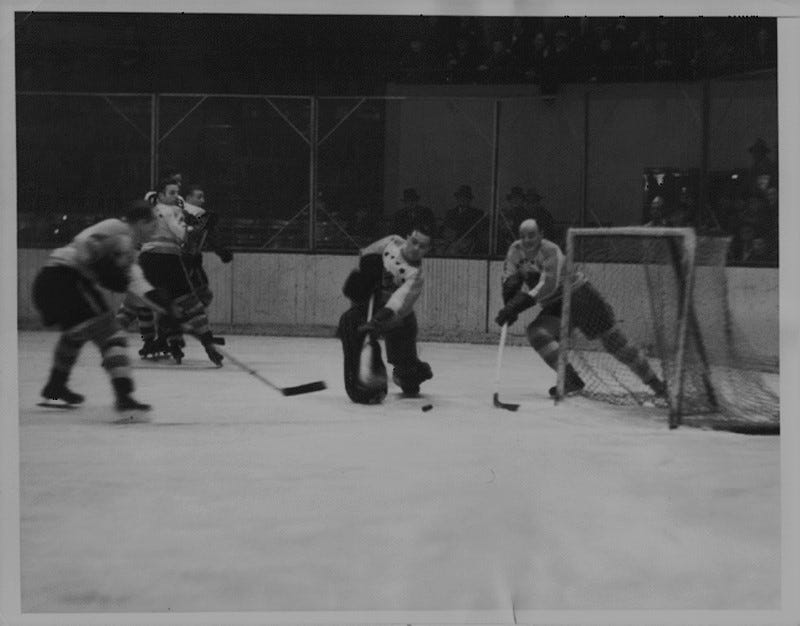

Ching Johnson is regarded as one of the hardest bodycheckers to ever play the game. In his time he was up there with Eddie Shore as the top defensemen in hockey. He was built so much like a brute at 5’11” and 210 lbs, that when Ching connected with an unsuspecting target, it was like being hit by a train. Ching wasn’t a dirty player like so many were at his time, he was just a terrifically hard hitter.

Possibly the best defensive-defensemen the game had seen up until that point, the Hockey Hall of Fame website writes that, “It was his physical play and his charismatic leadership that made Ching one of the most valuable rearguards of his time.”

Johnson was a fierce competitor who ignored the pain and didn’t let injuries stand in his way. One of the most colorful players of his generation, he always had a wide grin on his face whenever he went to crunch an opposing player to the ice. More significantly, he perfected the technique of nullifying the opposition by clutching and grabbing them as discreetly as possible – a pragmatic defensive strategy for the wily but slow-footed rearguard.

Fellow Hockey Hall of Famer and Rangers teammate Bill Cook once claimed that Johnson was the greatest hockey player he’d ever seen.

“Prematurely bald, Ching was the kindest, most gentle man you would ever meet off the ice,” wrote long-time Winnipeg Tribune writer Vince Leah. “He had a marvelous smile that captivated people. He had time for everybody, young and old. But when he clobbered incoming attackers, he would turn an impish grin as if he had snatches the last cookie out of the jar.”

A two time Stanley Cup winner (1928 and 1933), Johnson was a fan-favorite in the Big Apple, but also a late bloomer of sorts as he didn’t play his first NHL game until he was nearly 28 years old.

“Ching was not what you’d call a ‘picture player’ − he wasn’t a beautiful passer or stickhandler − but he was one of the hardest hitters in the history of the game, a great leader, and an absolute bulwark on defense,” recalled former teammate Babe Pratt. “He’d hit a man and grin from ear to ear and he’d be that way in the dressing room, too. There was never a time when Ching didn’t have itching powder in his pocket, ready for a practical joke. One time he gave Lester Patrick a hotfoot and Lester’s shoe caught on fire; Lester was half-asleep at the time and after they put out the fire he couldn’t walk for a week. It took a lot of nerve to do that to Lester Patrick.”

Ivan “Ching” Johnson was born in Winnipeg on December 7th 1897. Growing up in a house at 287 Stradbrook Avenue in Fort Rouge, Ivan played hockey recreationally with his brother Ade (Adrian) from a young age, but throughout his youth he was more focused on other sports like lacrosse and football as he excelled at both of them.

When Ching was just eighteen years old he joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force for World War I and fought for three years in the trenches of France as part of the mortar outfit. Johnson returned to Winnipeg after the war and worked for an electric light company, in addition to attending classes at the University of Manitoba. It wasn’t until Johnson got home from the War that he really decided to get into hockey. He played his first competitive hockey game when he joined the Winnipeg Monarchs senior team in 1919 as a twenty-one year old. He played only on outdoor rinks until after the War and he quit high school to enlist for World War I in 1914. Came out of the war in June 1919.

In the early 1920’s, the town of Eveleth on the Mesabi Iron Range of northern Minnesota sought to improve hockey in the area by bringing in players and giving them mining jobs. Ching and his brother Ade joined the Eveleth Reds team in 1920 and spent three seasons playing amateur hockey on the Iron Range. In 1923, the brothers were picked up by the Minneapolis Millers of the same league and they played a few more seasons of amateur hockey.

It was while playing in the minors where Ching earned his nickname. First he was known as “Ivan the Terrible,” but fans quickly took notice of the fact that when he smiled, his eyes made him look Asian despite him being of Irish descent. Fans would shout “Ching-a-ling Chinaman!” and that eventually got shortened to just “Ching.” The nickname would stick for the rest of his life.

The name “Ching” has stuck with him since his teenage years in Winnipeg. There had been an outdoor rink in the backyard of the Johnson home. “Ching” and his brother “Ade” and the boys of the neighbourhood, made a habit of using the Johnson kitchen as a dressing room.

Finally, Johnson’s dad created a small dressing room in the backyard in order to save the kitchen from destruction. This became the official clubhouse of the “gang.” Time came when the boys started to cook their meals in their new headquarters between hockey matches. Ivan was appointed chef of the outfit. Then came the nickname of “Chinaman” for the big fellow. That name became too long and soon it was “Chink” Johnson. From “Chink” the nickname developed into “Ching,” and it has been “Ching” ever since.

Ching caught his big break in 1926 when he was first discovered by Conn Smythe during a scouting trip to Minnesota. Smythe had been hired to recruit a team for the expansion New York Rangers team and was supposed to manage the club for their inaugural season. He really liked both Ching and his defense partner Taffy Abel, but found Johnson to be a tougher negotiator than anything he’d ever seen before.

“I must have reached an agreement with Ching forty times,” recalled Smythe. “Each time, when I gave him my pen to sign, he’d say, ‘I just want to phone my wife.’ Then there’d be a hitch, and he wouldn’t sign. In my final meeting with him, I said before we started, ‘Ching, I want you to promise that if we make a deal, you will sign, and then you’ll phone your wife.’ He promised. We made a deal. He said, “I’ve got to phone my wife,’ I said, ‘You promised!’ He said, ‘Okay, Connie,” and signed.”

Johnson was apparently adamant on signing a three-year deal because he thought it would be the only one he would ever get. He had no idea how well he would fare joining the fray of what is the National Hockey League. Conn Smythe never got to enjoy Johnson on his club as he was dumped before the season even started by the Rangers owner and replaced with Lester Patrick.

Ching made his NHL debut just before his 28th birthday. A late bloomer some would say just by looking at his age, but for Ching, he came in at the right time and was a force in the National Hockey League from game one. He quickly became the team’s leader, both for his enthusiasm on the ice and his take-charge, rah-rah manner in the dressing room.

A fan-favorite from his booming body-checks and physical play, Sports writer Al Laney of the old New York Herald-Tribune claimed that only Babe Ruth equaled Ching Johnson in winning the hearts of fans in New York City.

“Ching loved to deliver a good hoist early in a game because he knew his victim would probably retaliate, and Ching loved body contact,” recalled Frank Boucher. “I remember once against the Maroons, Ching caught Hooley Smith with a terrific check right at the start of the game. Hooley’s stick flew from his hands and disappeared above the rink lights. He was lifted clean off the ice, and seemed to stay suspended five or six feet above the surface for seconds before finally crashing down on his back. No one could accuse Hooley of lacking guts. From then on, whenever he got the puck, he drove straight for Ching, trying to out-match him, but every time Ching flattened poor Hooley. Afterwards, grinning in the shower, Ching said he couldn’t remember a game he’d enjoyed more.”

Throwing his body at every player of course had its consequences. Throughout his career he spent over thirty weeks recovering in a hospital bed from his hockey injuries. A broken collarbone, damaged ribs, broken jaw, and a cut-open forehead was just a small portion of what he endured. In total he had 27 broken bones and close to 400 stitches over the course of his career.

On one occasion while he was at the Montreal General Hospital recovering from a broken ankle, a fire broke out and he had to escape. Luckily, Ching had a visitor at the time of the fire (goaltender Lorne Chabot’s brother) and with the help of orderlies, Ching was carried from his second-floor room down a fire-escape, outside, and to a friend’s nearby apartment. When Johnson returned after the fire ceased, a newspaper wrote that, “on the shoulders of his stalwart supporters, greeting the staff with a typical good-natured wave and an announcement that he had returned.”

In his third year in the NHL, Johnson helped the New York Rangers with their first Stanley Cup in team history. He won a second Stanley Cup in 1933 and by that time he was widely regarded as one of, if not the best defensemen in hockey. Without Ching manning the blueline, it’s very unlikely that the Rangers would have won either Stanley Cup.

While playing in New York, Ching had a place in Yonkers that his kids grew up in. His son Jim remembered that during the season his dad would have these grotesquely swollen knuckles all winter long and usually a broken bone to go with it. Jim recalled that, “One time he had broken his jaw and I had broken my jaw at the same time playing college basketball at Marshall University. Both of us had our jaws wired shut and I remember sitting across the table from him, both of us dribbling baby food down our shirts.”

Johnson finished as the 1932 Hart Trophy (NHL’s Most Valuable Player) runner-up by one vote to Howie Morenz. He finished his NHL career after the 1937-38 season with the New York Americans and “retired” at age 41. He continued as a player-coach until he was 46 for minor-league teams based in Minneapolis, Marquette, Washington and Hollywood.

In twelve NHL seasons, Johnson finished with 86 points in 436 games. His two Stanley Cup’s in 1928 and 1933 were his best accomplishments, but he was also an NHL First Team All-Star three times (1928, 1932, 1933) and a Second Team All-Star on two occasions (1931, 1934). He played in the inaugural 1934 All-Star Game in benefit of Ace Bailey and was voted as the most outstanding player on both Rangers Cup teams that he was a part of. Ching also led the Rangers in penalty minutes in eight of the eleven seasons he played with them.

After he retired, he coached in the minors and then later officiated. During one Eastern Hockey League game in Washington D.C. that he was officiating, fans saw the hard-hitting Ching Johnson one more time. “I was calling this game,” recalled Ching, “when some young forwards broke out and raced solo against the goalie. Instinctively, I took this player down with a jarring bodycheck. Following the game, I apologized to his team. I don’t know what made me do it, but I did it. I guess it was just the old defenseman’s instinct.”

After his stint in Washington, Ching decided to move to California where promoters were trying to get hockey started in The Golden State. One day he was spotted skating on a local rink in Hollywood and was asked him to play for their minor league team. Ching was on a championship team in 1944 at the age of 46 when the Hollywood Wolves won the league and national title.

After he finally left the game of hockey for good after putting in his twenty-five years, he became a general contractor in the construction business in Washington D.C and later ventured in the plumbing, heating and air conditioning business. He attended Washington Capitals games periodically when they came into the league in 1974 up until his death. Ching’s passion for the game never died as he was still skating well into his seventies.

During his career Johnson always had great pleasure coming back to Winnipeg every year for the New York Rangers training camp at the old Amphitheatre since that’s where his games were when he first started out in competitive hockey with the senior Winnipeg Monarchs. Ching never lived in Winnipeg after he made the NHL, but he still made a point in coming back home throughout his life to visit family and friends.

Ching’s career was honoured in 1958 when he was inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

In his later years, Johnson and his wife resided in Takoma Park, Maryland. He passed away in nearby Silver Spring on June 16th 1979 at the age of 81.

“He always wore a grin,” recalled teammate Frank Boucher, “even when heaving some pour soul six feet in the air. He was one of those rare warm people who would break into a smile just saying hello or telling you the time.”

Once again, thank you to Ty Dilello for allowing me to share this awesome article with you guys!

LET’S GO RANGERS!

Sean McCaffrey

BULLSMC@aol.com

@NYCTHEMIC on the Tweeter machine